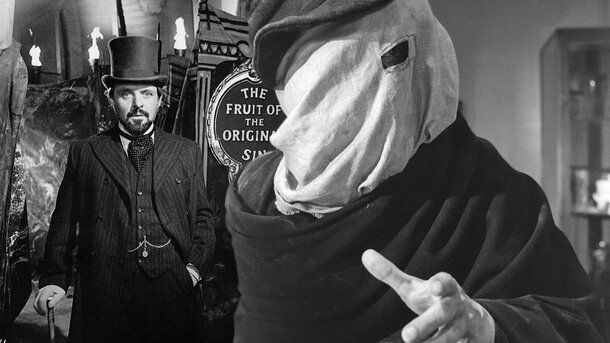

David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (1980) remains one of the most affecting films in British cinema — a stark, monochrome exploration of what it means to be human beneath the surface. Based on the real life of Joseph Merrick (often mistakenly called John), the film recounts the story of a severely disfigured man who lived in Victorian London and became both a medical curiosity and a reluctant symbol of compassion.

Merrick, portrayed with heartbreaking subtlety by John Hurt, suffers from what modern researchers believe to be a combination of neurofibromatosis type I and Proteus syndrome — rare conditions that caused severe deformities.

The film follows his journey from being exhibited in freak shows to being rescued and cared for by Dr. Frederick Treves (played by Anthony Hopkins). As Merrick begins to reclaim his humanity, society’s cruelty — and kindness— become impossible to ignore.

The Elephant Man ends on a devastating but poetic note. Having experienced dignity and friendship for the first time in his life, Merrick chooses to sleep lying down — something his condition made perilous. He dies in his sleep, likely due to asphyxiation. The final scene fades into a quiet celestial vision, underscoring the grace Lynch finds even in sorrow.

The film was released in 1980, but Merrick himself was born in 1862 and died at just 27, in 1890. More than four decades on, The Elephant Man still asks the same painful, profound question: who is the real monster — the man with the disfigurement, or the world that cannot see past it?